Reproductive Exile (4K video, 30 min with 5.1 surround sound, 2018-2023)

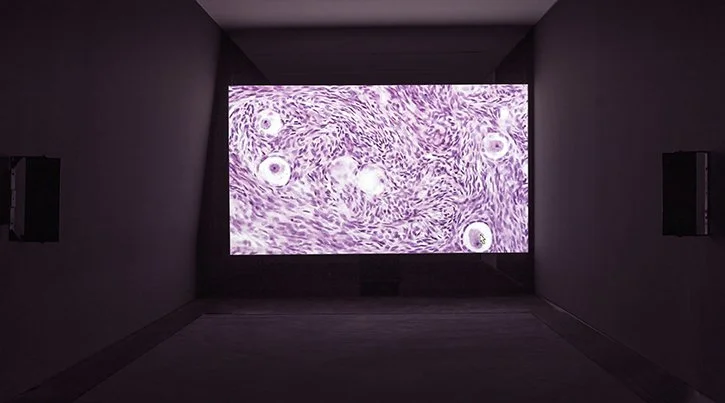

The film tracks the experience of a cross-border patient in the commercial surrogacy industry where we encounter this “reproductive exile” on the road, in her car, obsessed with a machine called ‘Eve’—a scientific prosthetic assigned to her as a personalised organ model who she confides in while swabbing, driving, and injecting herself in a seemingly endless loop. In a drug induced hallucination she imagines her inner body flooding - mirroring a medical state referred to as ‘third spacing’ which is an exaggerated response to excessive hormones in which fluids collect in the interstitial space between cells. In this state of overflow the protagonist experiences her body conflated with the nonhuman others that facilitate her fertility treatment, including the pregnant horse whose urine is a resource material for the drugs she injects daily. This film was commissioned by Lafayette Anticipations Paris, Tramway Glasgow and De La Warr Pavilion, UK

Trying to Conceive by Naomi Pearce

1 FICTION

What kind of license does this fictive framework provide? Reproductive Exile collapses the binary of subjective artwork and objective science not to offer an alternative to expert discourse but to intervene within it, positioning itself in what Susan Squier has described as somewhere “between knowledge and unawareness.” 1 In this sense, Lucy uses film to create subjects out of scientific objects. I rewind the sequence of CT scans and watch them on repeat. Female torso, horse’s hoof, mouse. Instinctively I see a face as the glowing orbs of her hip bones morph into two eyes, the sharp slit of her labia a crooked smile. Her edge is a halo of white casing, marbled blue bacon fat. The camera is cutting through tissue, seeing where we can’t see, melting through layers going deeper. Without her skin she’s a swirling mass of shapes, an abstracted Magic Eye picture. Lucy is not a medically trained professional nor the intended viewer of these images. I understand her misuse of this material as following the approach of Roberta McGrath whose research into mid-nineteenth century medical photography tries “to understand the female body in its historical corporeality, rather than its biological specificity.” 2

In case you didn’t know, Evatar exists, just not quite how Lucy imagines it (well not yet). I visit the website of Woodruff Lab at Northwestern University where this organ chip is under development. Here the real Evatar is a dull orange plastic, not stainless steel, and its liquid culture is blue rather than flaxen. Predictably, the researchers are quick to gender: “She’s innovative. She’s three-dimensional. She’s made out of human cells. She has a functional reproductive tract that includes an ovary, fallopian tube, uterus and cervix. She also has a liver, and the channels necessary to pump nutrients between her organs. She produces and responds to hormones, and has a normal 28-day hormone cycle. She can metabolize drugs. She can tell you how a drug may affect fertility in women, or if it is toxic to the liver. And she fits in the palm of your hand. She’s the future of drug testing in women and personalised medicine, and her name is Evatar. Just as Eve is thought to be the mother of all humans, Evatar is the mother of all microHumans.” See how science relies on fictions too.

2 MCGUFFIN

The question I really want answered is who are the bad guys in Reproductive Exile? States and countries with restrictive reproduction regulations? Scientists with their invasive and cruel animal testing? The essentialist thinkers who assume sacrifice and suffering are part of the female condition? Those who advocate the free market individualism of assisted reproduction technologies? The people desperate to have a baby that “resembles them”? Lucy’s protagonist Anna is a witness, not a heroine and she doesn’t offer us answers. I love her face, how it refuses access to her thoughts despite its translucent skin. Gapped teeth, hair finer than mine, she has the kind of look my mum would describe as ‘interesting’. Anna’s resistance to communicating with the humans who prod and probe her keeps me invested. She lets us in through her correspondence with Eve. I’m interested in how these monologues are preoccupied with process and not outcome. As I watch, I forget she’s doing this work for a baby. Maybe this film isn’t about pregnancy, it’s about reproduction. Maybe the baby is a McGuffin?

McGuffin: a plot device in the form of some goal, desired object, or another motivator that the protagonist pursues, often with little or no narrative explanation. The McGuffin’s importance to the plot is not the object itself, but rather its effect on the characters and their motivations. By the end of the story the McGuffin may be forgotten altogether.

3 COMMUNION

I start to think about The Handmaid’s Tale during my third viewing. To clarify, I mean the novel written by Margaret Attwood (not the TV series) set in the totalitarian society of Gilead in which ’Handmaid’s’ are enlisted to bear children for the elite. I could make a few clunky connections: the shared infertility and surrogacy narratives, an interest in the power and agency of reproductive relations. But what intrigues me more is their mutual summoning of invisible women. Early in Attwood’s book the protagonist Ofred finds a message in her bedroom: “Nolite te bastardes carborundorum,” faux Latin for “Don’t let the bastards grind you down.” Later she learns this phrase was carved into the floorboards by the previous Handmaid, shortly before she hung herself from the room’s chandelier. But on first encounter with the phrase, ignorant to its origins and buoyed with momentary relief from her loneliness, Ofred is pleased to be communing with an unknown woman. She speculates as to whether she used a pin or a fingernail to etch the message and is thankful for this woman’s desire to reach from the past into her present. She asks: “What’s become of her?” 3 Reproductive Exile speculates on the many invisible women in the fertility industry, from the urine donors providing hormones or the brokers who labour behind the scenes to the surrogate hosts. As Anna begins to correspond with Eve, her bespoke scientific prosthetic, reproducing her menstrual cycle, I feel the film shift. After this first meeting it is as though the tone, colour and speed of her life is forever changed. We see Eve reflected in the watery violet of Anna’s iris, hear the voice of the clinic co-ordinator receding into a muffled hum. A piercing, singular focus descends. In my notes I write ‘love letter’. Anna, like Ofred, feels desperate for communion. In this near future imagining, mammal and machine mingle, rub up and into each other, Anna’s words searching in a forbidden way pregnant with desire. “Desire is not simple,” 4 writes Anne Carson. In Greek, love is a mingling (mignumi), desire challenges the boundaries of bodies; “The god who melts limbs precedes to break the lover (damnatai) as would a foe on the epic battlefield: Oh comrade, the limb-loosener crushes me: desire (Archilochos, West, IEG 196).” 5 In Reproductive Exile Anna and Eve mingle, loosening each others limbs. They come together in shared technical status. Anna is conscious of the other bodies to which she is intimately connected; the hormones purified from mare’s urine which thicken her host’s uterus, the hormonally active medication she injects extracted from the urine of menopausal women. She finds comfort in the sharing of this fluid debris. Take the scene where she is driving, the soundtrack is a dense layering of tremoring synths, some guttural others fizzing. These are overlaid with reversed noises: buzzing electrical currents, beeping machines, the muffled echo of watery submersion. A dull heartbeat quickens as liquid rises in test tubes. Synthetic and organic dissolve. The images move between Anna falling asleep at the wheel, head bobbing, the tunnel’s overhead lights turning her skin the colour of weak tea, and Anna under anaesthetic in the clinic, lying on a gurney. These shots are broken with dreamy visions of Eve. Previously the camera presented her in totality, rotating objectively above. Now it floats inside one of her metal organs, half submerged, rocking in a sea of liquid. Lucy’s notes to Grader: the colour of morning wee. As a deep rumble builds, Eve overflows. Cut to white slender legs, glowing in what looks like a bath of mare urine. Gasping breath, the sound of rushing car horns, near fatal collision and then Anna’s voice: “We’re soaking in each other.” It’s a climax of sorts, my preferred alternative: “they get wet together.”

4 WHITE

Like Attwood’s Gilead, Reproductive Exile seems to unfold within the context of a white supremacy. Although it is not explicitly referred to as such whiteness inseminates the film’s images. White mouse fur, lab coats, sperm. White bedsheets, latex, ear buds. White walls, radiators, clock. White quarry of Kaolin to purify the biological hormones used by the clinic. Proteins and contaminants removed. White skin of the clinics co-ordinators, the Intended Parents, the phantom surrogates. I text Lucy: Hey can you send me any factual essays etc about the surrogacy/IVF process that you found useful? Thanks bb xx She responds quickly, emailing a link to a Googledrive entitled ‘LUCY Research’. I open it, a column of neatly organised folders: Court Decisions, LEGALITIES, Parliamentary and ECHR reports, READING MATERIAL. These are followed by a stack of word documents including a couple of helpful crib sheets with titles like ‘Surrogacy in the World’ and ‘Different Legal Cases’. I am overwhelmed. First by the volume; the pages of datasets, personal testimonies, scientific and political legislation, then by the complexity. As Anne Phillips writes in Our Bodies, Whose Property?; “We cannot do any kind of work without dragging the body along, and a prohibition on the sale of any services that involve the body would make no sense at all.” 6 Lucy points me to the pdf Intimate Labor Within Czech Clinics, a chapter from the book Fertility Holidays by medical Anthropologist Amy Speier. I start to read it over morning coffee, my eyes struggling to focus. Speier writes of the ways in which cross-border reproductive care reflects a global stratification that empowers some to nurture and reproduce whilst disempowering others. I think of the fictional dystopian future of Attwood’s Handmaid’s and then surrogacy’s real dystopian past, the one which belongs to Black southern mothers enslaved in American plantations where, as argued by Anita L. Allen, they “knowingly gave birth to children with the understanding that those children would be owned by others.” 7 A subsection of Speier’s essay, ‘Choosing White Babies’, describes how a couple’s skin colour determines their travel route for fertility care; “couples choose the Czech Republic for white egg donors, for ones who will resemble them.” 8 I recognise the words ‘resembles them’ from Lucy’s script. Is now the time to tell you that I have never been pregnant? To say that I do not know if I am able to get pregnant. To admit that I am ambivalent about pregnancy. To speculate that I am unsure as to whether I will reproduce. Does this matter to you? Does it make a difference to this text? For some reason I need you to know.

5 CYCLES

I find women online documenting infertility journeys and spend too many hours watching their YouTube videos. I am sad eyed and open mouthed, a knot of alienated empathy. I scroll through the comments, streams of other women sending wishes of good luck and “baby dust”.9 These self defined TTC’s (trying to conceive) turned investigators surveil their own innards determined to demystify biological events with daily temperature checks and fertility calendars. In this repetitive monitoring — daily, weekly, monthly — understanding the body’s temporal logic is presented as a means of mastering it. As someone living with a chronic auto-immune condition, I can’t relate to their shock; I have never assumed my body would work ‘correctly’. Disgusted by my voyeurism (what is so addictive about other people’s pain?) I go back to Google and click on the article ‘7 things every woman should know before freezing her eggs’. Just as hair follicles loose pigment, ligaments stretch or skin sags, eggs age. “The most important thing for eggs is time,” says endocrinologist and infertility specialist Dr. Jaime Knopman. The younger the better, all scientists agree. Age is more than just a number at our most microscopic, it is our ability to replicate. I think of my own engrained assumptions concerning productivity and youth. If ‘time is money’ in what ways is the body clock’s ticking not simply wasteful, but bad for business? As Jasbir K. Puar writes in The Right to Maim: Debility, Capacity, Disability; “Neoliberal regimes of biocapital produce the body as never healthy enough, and thus always in a debilitated state in relation to what one’s bodily capacity is imagined to be.” 10 I ask Siri: “How long can a frozen embryo survive?” She replies: embryos can remain viable for many years with cases of live birth resulting as long as 15 years after freezing. Biomedicine intervenes with time, it stops, starts, reverses. Lucy also screws with chronology, playing scientist by avoiding a beginning and end, in favour of the loop. The loop as an endurance strategy which unlike the aging body never tires. The loop resists closure, automatically replaying to fend off disappointment. Reproductive Exile explores the concept of time as something which both inevitably passes but is also unpredictably unknown. Cycles multiply: Anna’s, Eve’s, horse, mouse: all syncing together. It’s disconcerting to stay in the space of this film. It may be ruled by time but it is also stuck in its own rhythm.

6 LIMINAL Is there a more liminal position than that of the reproductive tourist? These persons away from home seeking the gestation of new life. They wait to expect and expect to wait. See the suitability of military wives as surrogates. But whereas ‘tourism’ implies leisure travel, reproductive ‘exile’ alludes to the numerous difficulties and constraints faced by infertile patients who are ‘forced’ to travel globally for assisted reproduction. Lucy shot Reproductive Exile on location in the Czech Republic, a now prime destination for IVF and surrogacy in the wake of countries such as Thailand, Cambodia, Nepal and others closing their borders to international clients. She tells me at the root of this film is her interest in the perpetual relocation of the global fertility industry, its liminality, how it is reshaped as ethical approaches change and laws processually develop.

7 SUSPENSION

Astrologically speaking this film is a water sign. Liquid seeps, oozes, gushes and floods. It leaves bodies as piss or blood. It circulates architectural structures, pouring from taps and fountains, filling baths and swimming pools. Instead of symbolic wombs in the form of vessels or containers, Lucy focuses on fluid as a substance which connects but also flows. She traces bodily revenue streams. Even the visual effects designer who worked on Eve is a specialist in creating digital models of vicious fluids. I can’t decide whether this metaphorical use of liquid is sinister or soothing. I think of the black abyss in the film Under the Skin with its shells of imploded men, suspended, coaxed to their watery ends with hard cocks and inflated egos. In Reproductive Exile liquid connects but it also overwhelms, Eve drowns whilst Anna loses consciousness. Lucy tells me she almost called the film Hyper Stimulation a term for the condition that arises when women over stimulate their ovarian follicles to try and produce more eggs. This overstimulation leads to fluid moving into a third space within the body; the interstitial, non-functional space between cells. The severe consequences of this are fatal, but in more common mild cases, phantom bloat babies grow and women look like they’re in their second trimester. What cruel design the body has. These liquid pregnancies point to another kind of suspension at work in Reproductive Exile, that of disbelief. As with Lucy’s previous work this film performs the documentary as fiction: she writes a script set in a fictional clinic with fictional co-ordinators who workshop real-life scenarios. Surrogacy too in some sense begins with a fiction, that of the intended parents fertility and their future family unit with a child who “resembles them”.

8 BABY DADDY

We never find out where Anna gets her sperm from. Aside from the audience at the horse show, when men do appear on screen they inseminate or inject. One is proficient; hand sleeved in plastic sucked deep inside a mare, the other a bit useless; “Oh there’s blood”, he squirms at the site of his partner’s oozing red flank. “Go get a paper towel” she signs, despondently. These images evidence the influence of industry and the ways in which, as Roberta McGrath has argued; “through biotechnology, sex is now finally and irreversibly severed from reproduction.” 11 I find all the scenes with animals difficult to watch, depicted as they are either in captivity or under restraint. In earnest I start reading Ulrich Raulff’s Farewell to the Horse: The Final Century of Our Relationship. The chapter ‘Blood and Speed’ describes the origin of The Stud Book: a genealogical peerage of the English thoroughbred. Like me you probably didn’t know a book concerning the nobility of horses preceded that of the nobility of Englishmen. Maybe you are also less amused to learn that horse breeding and the desire to manipulate human genetics have a history. The practice inspired Francis Galton, the founding father of eugenics: “In 1883 [he] acknowledged the contribution of English horse breeders to his research. Their experiments had shown how suitable breeds or bloodlines could be helped to prevail against the less suitable. […] Targeted tampering with genetic inheritance in order to improve a breed: this was the great dream of the eugenicists of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. But as they themselves admitted, the birth of this dream came much earlier: in the stables of the eighteenth century” 12

9 TRICK

This film is about much more than two bodies becoming one and one body becoming two. Opening scene: close up of an artificial mare also known as a phantom mount. Surface scratched, puckered, evidence of previous contact. It’s made of leather: the hide of a dead cow. Birds tweet, the atmosphere is calm and bright. Camera is static, personifying the artificial mare’s availability, how she must wait. A stallion enters the frame, he has the agency to move. She heaves under his weight, creaking like an old bed. He is fucking the skin of a dead cow. Open mouthed, a globule of foamy spit trailing, he thrusts mechanically. Later it’s the mare’s turn to be tricked. Anna meets her via a floating monitor screen, chestnut head looming large, bathed in blue light. An equine breeding website tells me the blue light is tricking her circadian rhythms to optimise and regulate fertility. As the clinic’s lead co-ordinator states, in countries such as France surrogacy is a prosecutable offence, considered a kind of trick on the grounds that it ‘simulates’ the mother. Her response to legislation is one of negotiation; ‘We need to work around these fixed definitions of motherhood,’ she says. Redefining roles is yet another task on the gestational labour to do list. Perhaps the greatest trick baby making still manages to perform — despite us knowing better — is the illusion that it happens ‘naturally’. In some way, all reproduction is assisted, as Sophie Lewis has succinctly argued; “It takes lots of work from lots of people to make and remake us, before and after we are born.” 13 In Reproductive Exile, Lucy’s preoccupation with the trick is not to reinforce the binary of ‘natural’ and ‘unnatural’, assisted or unassisted, it is to expose the fantasy on which this restrictive system is built.

Naomi Pearce is a writer, curator and administrator who collaborates with artists to make exhibitions, essays, books and events. Recurring themes include the politics of artistic production and gentrification as they intersect with feminist legacies, death and discourses of desire.

This text was published by Lafayette Anticipations to mark the premiere of Reproductive Exile in June 2018.

Notes

1 Susan Squier, Liminal Lives: Imagining the Human At The Frontiers of Biomedicine (Durham: Duke University Press, 2004), 22

2 Roberta McGrath, Seeing Her Sex: Medical Archives and the Female Body (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2002), 2

3 Margaret Attwood, The Handmaid’s Tale, (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 1986), 53

4 Anne Carson, Eros the Bittersweet: An Essay (New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 2014), 7-8 5 Ibid

6 Anne Phillips, Our Bodies, Whose Property? (New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 2013), 30

7 Anita L. Allen, “The Black Surrogate Mother”, Harvard Blackletter. Spring 8 (1991), 17–31

8 Amy Speier, Fertility Holidays: IVF Tourism and the Reproduction of Whiteness (New York: NYU Press, 2016), 74

9 “Baby Dust: is a term meaning good luck with conceiving a baby and a hope that it will happen soon. Sticky Dust is a term meaning good luck with a current pregnancy, in hopes that it ends with a healthy baby. This is commonly used when a mother has had a previous miscarriage”, Trimester Talk, accessed 9 August, 2018 http://trimestertalk.com/ what-is-baby-dust-or-sticky-dust/

10 Jasbir K. Puar, The Right to Maim: Debility, Capacity and Disability (Durham: Duke University Press, 2017), 82

11 Roberta McGrath, Seeing Her Sex: Medical Archives and the Female Body (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2002), 36

12 Ulrich Raulff, Farewell to the Horse: The Final Century of Our Relationship (London: Allen Lane, 2017), 155

13 Sophie Lewis, “Mothering”, Boston Review, 14 August 2018, http:// bostonreview.net/forum/allreproduction-assisted/sophie-lewismothering (accessed 28 August 2018)